Is Poverty like a Pond?

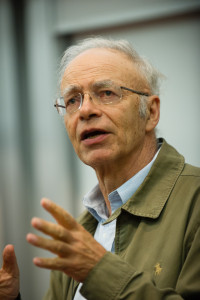

In a famous 1972 article, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” philosopher Peter Singer compared global poverty to a child drowning in a pond:

[I]f it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing

anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it. An application of this principle would be as follows: if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a

very bad thing. (231)

If we ought to prevent something very bad from happening whenever we can do so without sacrificing anything morally significant, then we also ought to spend much of our lives and wealth on rescuing people from starvation and disease:

It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor’s child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away. . . [We should make] no distinction between cases in which I am the only person who could possibly do anything and cases in which I am just one among millions in the

same position. (231-2)

Instead of buying a Starbucks coffee once a week, you could save that money – about $200 over the course of a year – and give it to a charity that saves lives. It’s morally wrong to buy Starbucks coffee when there are people dying around the world. Letting someone die so that you can enjoy Starbucks is like letting a child drown rather than getting your suit muddy.

It doesn’t matter that most other people aren’t living up to their moral obligations. Bystanders’ failure to save a drowning child doesn’t relieve you of a duty to save that child. If you can save a life without sacrificing anything morally significant, you must.

What should we make of this argument? The analogy between saving someone from extreme poverty and saving a drowning child seems strong. Millions of people around the world die young (or at birth) due to disease and malnutrition. We in affluent countries spend much of our wealth on luxuries. In fact, we eat too much and watch too much TV. Can’t we afford to spend a lot of that wealth on helping save others’ lives? And if we can afford it, don’t we have an obligation to do it?

Singer’s argument faces two main difficulties. First, he thinks it’s obvious that consuming luxuries isn’t morally significant. But is that right? Perhaps having your once-a-week Starbucks can be as morally significant as saving a life, strange as that may sound. Second, he thinks saving poor people’s lives is about as simple as wading into a pond and dragging a drowning child out of danger. But in fact it might be a lot more complicated.

Let’s think about the first point. Global poverty is a really big problem. There are millions of people suffering from extreme poverty and a very high likelihood of early death. If it were always wrong to consume a luxury whenever there were someone whose life could be saved instead, we would in fact be morally obligated never to consume any luxury, and to spend essentially our whole surplus wealth and time on saving people. It’s as if there were millions of ponds with millions of children drowning in them. To live up to a moral duty to save every life, we’d have to spend our entire lives going from pond to pond.

That kind of life might not be worth living. You’d be turning yourself into a virtual slave of the people you save. Your life would have no value to you, because you would have no opportunity to put an individual stamp upon your plans, projects, and desires. Your whole life would be predetermined from the outset: work as hard as you can so that you can save as many people as you can, and never do anything else.

You might have a duty to save lots of people without having a duty to forego all the pleasures that make life worth living: making friendships, developing hobbies, reading, creating, and, yes, even consuming. A once-a-week Starbucks might actually be morally significant to your personality (to me, it would be my home-brewed cup of oolong, but preferences vary). It isn’t clear at what point it becomes morally permissible for us to focus on our own desires rather than spending our resources on saving others, but it’s definitely well before the point of “marginal utility” (when you become as bad off as someone in extreme poverty). The point isn’t that you don’t have a duty to save people – you do – but there are limits, real though difficult to nail down precisely, to the duty.

The second point is that saving people isn’t simple. Giving money to a charity that claims to help people may not do very much good and may even do net harm. Extreme poverty in the world today is generally the fault of some human organization or institution, usually a government but often rebel groups, gangs, and other purveyors of violence. People lift themselves out of poverty when they are free to trade and to enjoy the fruits of their labors. They remain poor only when they face violent threats to their lives, liberties, and property. If giving to a charity empowers some vicious gang or government that keeps people poor, you’ve just made poor people’s lives worse. This consideration doesn’t relieve us of the duty to give, but simply adds a duty to investigate seriously the consequences of our gifts before we make them.

To his credit, Peter Singer now realizes this problem, and the website he started, thelifeyoucansave.org, carefully evaluates antipoverty charities for efficacy. Most of the charities they highlight have shown, through randomized controlled trials, that their efforts are actually making people’s lives better. (I would take exception to the inclusion of Oxfam, which has been taken over by ideologues who seem to care more about rich-world politics than doing anything about real poverty.)

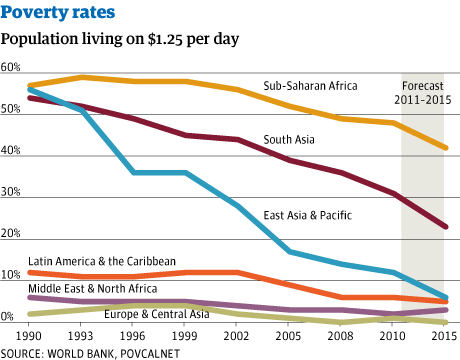

We do have duties to help those less fortunate, especially in developing countries, where extreme poverty of a kind we can barely imagine is all too commonplace. But we should also bear in mind that the biggest reductions in poverty haven’t come from foreign aid but from economic policy reform:

Extreme poverty is falling around the world, mostly because governments have chosen to let their people join the global marketplace. The biggest reductions in poverty have happened in China, where post-1980 market reforms have raised 680 million people out of poverty. One of the most important things we can do to better the lives of the poor is to fight for their access to property rights and to global markets.

Is the argument to help really so simple as you can so you must? What is the non-subjective foundation that justifies the argument? What is the counter argument if I assert that I disagree? Is this a pure utilitarian assessment that the life is more valuable than the coffee and so we must forgo the latter to protect the former?

Singer wants to be agnostic among foundational moral views. In other words, he just wants you to agree with the assumptions, whatever your reasons for doing so might be. Utilitarians could definitely agree with him (Singer is a utilitarian), but I could also see how someone could come to those assumptions through Smithian “sympathy” logic.

Thank you. I have read a bit of Singer and always have the same struggle of where to draw the line. He draws it at the point where any discomfort or loss is judged to be “morally insignificant” – my pant legs get wet and muddy but I’ve saved the drowning child or forgoing a Starbuck’s coffee and sending the $3 to a charity that helps feed starving child – and I agree in those examples. Who doesn’t? But real life is more involved and complicated as you so clearly point out. How about the fact that my willingness to pay $3 for a cup of coffee enables the employment of someone that would go hungry or not be able to afford shelter without the job? Shouldn’t that count in this moral calculus?

This has long been an interesting topic for me. I do like to help, and would never refuse to save that drowning child, but other than attributing it to “how I was raised” have struggled to explain why I feel such an obligation. Not being religious the whole god commands it argument is meaningless. And I find the various moral viewpoints (utilitarian, consequentialist, deontological) to be subjective and arbitrary.

Creating the job counts, but it’s less useful than just giving the money. Imagine that of the $3 you pay for your latte, $1.50 goes to wages, and the other $1.50 goes to materials (to simplify). Well, you could do more good, Singer would say, by just giving $3 to the worker, or better yet, giving $3 to someone near starvation in a poor country.

I have to say I’m a deontologist. I find the other moral methodologies lead to unacceptable conclusions. Deontology is objective because it derives the content of morality, which is binding on all rational creatures, from the concept of moral obligation (duty) and a few, spare intuitions that almost everyone would endorse.

I like the Starbucks analogy. Arguments against luxuries remind me of the song lyrics “Tax the rich, feed the poor; Till there are no rich no more?” Eliminating the rich, we’ll all be uniformly poor.

Interesting analogy. Does Singer have any idea how many people have “jumped in the pond” only to end up in GREATER danger than those they were trying to save?

Reducing your life to marginal utility also puts you at risk of falling into poverty comparable to the people you is trying to save. When you voluntarily place yourself on the economic boundary between debilitating poverty and the bare minimum that you need to survive, any sudden shift in your living situation can put your life and the lives of your dependents at risk. This would then require someone else to give you aid, and the cycle would continue. While sacrificing most of your wealth to help others is admirable, it may not be sustainable in the long-term.

He errs by assuming a power implies a duty.

He thinks in this case a power implies a duty, but not necessarily in all cases. His two premises are that death and suffering are bad, and that we should prevent death and suffering if we can do without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance.