The Notorious “B-I-G” Business…

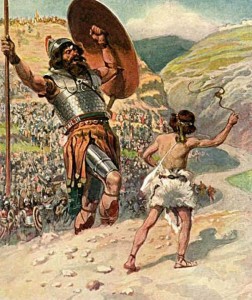

In many societies, there is a widespread antipathy of monopoly. The “little guy” is seen as noble, while the “big business” is to be feared or viewed with suspicion. “David” is the protagonist. “Goliath”: nemesis.

In many societies, there is a widespread antipathy of monopoly. The “little guy” is seen as noble, while the “big business” is to be feared or viewed with suspicion. “David” is the protagonist. “Goliath”: nemesis.

But in the field of economics the sentiment invites important questions, questions that offer surprising and fascinating answers.

For example, what does the term monopoly really mean?

Does a dominant company exploit consumers?

By offering products at a low price, is a dominant company engaging in unfair competition against other businesses?

Perhaps the best way to answer these questions is to understand the role economic competition plays in the market and our lives. As we discussed with students at E3NE, division of labor, private property and trade allow for prices to be determined, and for competition to begin. These, in turn, drive productivity up and prices down.

But when a company or seller dominates a field, we often hear that the company has a “captive market”; it’s a monopoly, which, we are told, is bad for consumers. The company will keep prices high. Big equates to bad, right?

Well, let’s look at how market entrepreneurs succeed and grow.

If consumers are free to buy or not to buy products or services, we can assume that they choose the company because they want the products or services and think them better values than others. Consumers make their own decisions, get price data from others and their trades, and help direct the flow of resources where they want them. Given these considerations, wouldn’t bigness result from doing good things for consumers? After all, folks could turn to a competitor, and make that competitor big.

From 1969 to 1982, the federal government launched an expensive antitrust investigation against IBM, only to drop it. IBM lost its dominant market position due to consumer choice, not government.

Detractors of the market might accept this logic, but still choose to believe that big businesses which have achieved large market share could do a number of evil things after they have been placed at the top due to market popularity. One of the first fears mentioned is that dominant companies could lower prices. Politicians call this anti-competitive or predatory pricing, which has a ring of strangeness to it. Is it true that lowering prices to attract consumers isn’t competitive? Has anyone ever seen a company increase its competitiveness by offering less to consumers and charging more? Sometimes, players in the political world can use very Orwellian language.

Detractors might say that this misses the mark. By “anti-competitive,” they mean that a company will lower prices to crush competitors, then, when attaining market “godhood” will raise prices and “gouge” consumers. As a result, it is worthwhile to see what happens when a seller dominates a particular sector of the market. Can he or she sell much higher than if he or she were just one of many in a field?

There are two important factors to consider here, the first being logical, the second being historical.

Logically, if a “dominant business” were to “crush” competition, then raise prices in an open and free market, such a move would send price signals to others, suggesting to them that there is profit to be found by entering that field. Thus, competition would return, forcing prices down.

Companies that become dominant in a sector typically continue to lower their prices, anticipating potential competition and working to become even more productive to stave it off. The so-called “Robber Barons” of American history who operated as market entrepreneurs are shown to have made their deals in order to lower prices and become more efficient. They didn’t rob at all. In fact, they continued to offer great savings and better living standards to consumers. They were always vulnerable to new competition, working to keep current customers and attract new ones.

“Okay,” detractors might say. “Perhaps the term ‘Robber Barons’ isn’t right. Maybe those business people lowered their prices… But couldn’t big businesses keep buying out competitors?”

No.

Engaging in such a practice merely increases marginal costs to a point where the business becomes uncompetitive and even more vulnerable to new market entrants.

Let’s move the issue into a more recognizable realm. If we are employees at a business, we don’t buy out potential competitors who might apply for jobs. We would go bankrupt. Instead, we perform; we offer better products and services to the people who hire us, and, likewise, businesses offer more to customers, the people who hire them.

There are two kinds of entrepreneurs, those who engage in peaceful, free-market competition (hence market entrepreneurs) and those who work to block competition the only way it can be blocked: through political means and statutes.

We call these latter players political entrepreneurs who game the system by getting lawmakers to block potential competition through passage of statutes and regulations. These blocks come in many forms: high tariffs against foreign competition, regulations that small upstarts cannot afford, licensing mandates that push out lower-priced competitors and limit consumer options, and more.

The truly “anti-competitive” activity people should fear comes when politicians favor certain businesses and block competition. This gives the favored recipient higher profits at the expense of the consumer, who is locked in a legal corral. Economists call this process rent-seeking. Rent-seeking means a political entrepreneur is attempting to gain not by offering greater value for a market trade with a consumer, but via a captive market made captive by political limitations on competition.

This is a loss for consumers, and is one of the most important lessons in economics. When people are free to find competitors, sellers compete to give them more for less. When political power looms over a sector, incentives twist, and political machinations favor the political entrepreneur over the consumer.

Bigness in a free market comes from serving the customer. Bigness in a political world of rent-seeking means that consumers are prey, trapped with limited options and no potential market entrants to provide competition.

When it comes to bigness, we should keep this distinction in mind. Goliath is only dangerous if all the Davids out there are prohibited from competing.